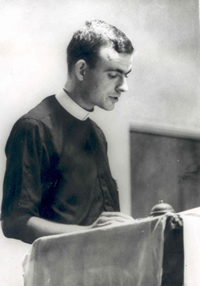

On August 14, the Episcopal Church celebrated the feast day of Jonathan Myrick Daniels. Daniels was born in 1939 and grew up in Keene, New Hampshire, the privileged child of a Congregationalist doctor. He became an Episcopalian in high school and attended the Virginia Military Institute, where he was elected Valedictorian. In April of 1961, Daniels received a profound religious calling and soon afterward decided to become a priest. A year and a half later, he entered the Episcopal Theological Seminary in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Daniels interrupted his seminary work in March of 1965 to heed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s call for supporters to join the protests for voting rights for black Americans in Selma, Alabama. Daniels stayed in Selma until it was time for him to take his exams, and he returned to Alabama that summer, working to integrate the Episcopal church in Selma and doing other social justice work. On August 13, Daniels participated in a demonstration in Fort Deposit, Alabama. That Saturday, he and his fellow protesters were arrested and jailed for six days in Haynesville, Alabama. Finally released on bail on August 20, he and three of his colleagues — a Roman Catholic priest and two young black women –went to buy cold drinks at a local store. A white man came out with a gun, confronted them, and shot at one of the girls, a seventeen-year-old named Ruby Sales. Daniels pushed Sales out of the way and was shot in her place. Hit in the stomach, he died immediately. Later, Dr. King would refer to Daniels’ sacrifice as “one of the most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry.”

Daniels’ life moves me partly because (unlike some of the more exotic saints), I understand Daniels’ life. My father’s life was a lot like Daniels’. My father was born a few months earlier than Daniels, attended a southern military college, and attended an Episcopal seminary to become a priest around the same time Daniels did. He was involved in the world of church clergy, dealing with the same issues, attending the same kinds of event. For all I know, my dad might have met Daniels.

Because of this sense of familiarity, I understand better with Daniels than with some other saints the temptation that he resisted to stay put and do nothing. He had every reason to ignore the call to go to Selma. He was safe and busy up in Massachusetts. Selma was both dangerous and comfortably far away. Daniels was in the middle of graduate school in preparation to become a priest, a calling about which he was very excited. It was not practical to go to Selma at all, let alone to get special permission to stay there and study on his own so as not to abandon the people there. He jumped through hoops to stay and still be allowed to sit for his exams that May. The whole thing was one big mass of inconveniences as well as protests and suffering — and inconveniences are great excuses to avoid suffering. Daniels faced down both the fears and the excuses to avoid God’s call and did what God wanted him to do. He stuck it out and died a martyr at age twenty-six.

Next month, from September 14-28, ChurchNext will be offering The Christian Response to Gun Violence, taught by The Eugene Sutton, Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of Maryland and Ian Douglas, Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of Connecticut, both outspoken advocates against gun violence. The course deals, not just with the fact of gun violence itself, but with what Bishop Sutton calls the “unholy trinity” that causes so many gun deaths: poverty, racism, and violence. Jonathan Daniels died fighting these demons. I hope that this course will give me and others the inspiration and information to continue Daniels’ fight in the new millennium.

in embracing the home- or hospital-bound recipients as participants in the congregation. He offers practical advice about what to bring to the visit, how to use the communion kit, how to report the recipient’s needs to the parish effectively, etc. He also offers valuable advice about the spiritual preparation involved in making an effective Eucharistic visit and about the approach one should take in discerning and responding to the true, deep needs of the care recipient.

in embracing the home- or hospital-bound recipients as participants in the congregation. He offers practical advice about what to bring to the visit, how to use the communion kit, how to report the recipient’s needs to the parish effectively, etc. He also offers valuable advice about the spiritual preparation involved in making an effective Eucharistic visit and about the approach one should take in discerning and responding to the true, deep needs of the care recipient.

Tim takes us back to the origins of lectoring and teaches us how the laity came to engage this sacred ministry. He offers valuable suggestions for preparing and proclaiming passages from scripture, including intellectual and spiritual ideas on how to better understand and convey the meanings of scriptural passages. The class also includes training on practicalities. Wondering what to do if the reading includes words like “Pi-Hahiroth” or “Zerubbabel”? Concerned about when to look at the congregation and when to look down at the reading (and not losing your place trying to do both at the same time)? Tim’s class answers these questions and many more. The class also includes valuable training about leading psalms and reading or leading public prayers.

Tim takes us back to the origins of lectoring and teaches us how the laity came to engage this sacred ministry. He offers valuable suggestions for preparing and proclaiming passages from scripture, including intellectual and spiritual ideas on how to better understand and convey the meanings of scriptural passages. The class also includes training on practicalities. Wondering what to do if the reading includes words like “Pi-Hahiroth” or “Zerubbabel”? Concerned about when to look at the congregation and when to look down at the reading (and not losing your place trying to do both at the same time)? Tim’s class answers these questions and many more. The class also includes valuable training about leading psalms and reading or leading public prayers.